Mapping the Surreal: A Conversation with Susan Rich

BY Jessica Gigot

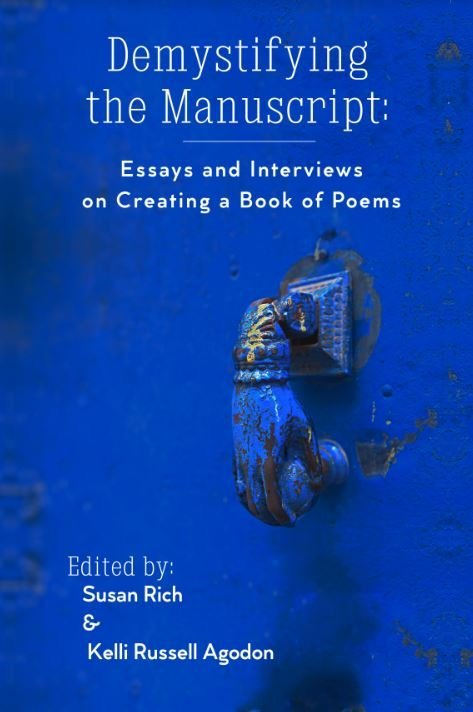

Susan Rich’s eighth book, Blue Atlas, is forthcoming from Red Hen Press (April 2, 2024). Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems (Salmon Poetry) and Demystifying the Manuscript: Essays and Interviews for Creating a Book of Poems (Two Sylvias Press), co-edited with Kelli Russell Agodon, both came out this past year. Rich is a professor at Highline College in Seattle, WA. She offers an annual poetry retreat for women called, Poets on the Coast.

Jessica Gigot: Your most recent book is Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems which was published in 2022. How did this book come together for you?

Susan Rich: It is a strange and circuitous journey. A friend who has published with Salmon Poetry approached me and asked if I had anything that I would be interested in showing the editor and publisher. Ilya Kaminsky had talked to me about the fact that he thought I should do a new and selected collection and this friend said that would be a great way to introduce my work to an Irish readership. They were going to Ireland in ten days and asked me to get a manuscript ready.

The poems were already written, but compiling something that felt like a lifetime’s worth of work seemed daunting. There are no books or essays on how to put together a new and selected collection. Kelli Russell Agodon and I have just released a book called, Demystifying the Manuscript: Essays and Interviews for Creating a Book of Poems, about how you put a poetry manuscript together, but this was a very different beast. I'm braver over e-mail than I am in person, so I decided that I would write Mark Doty, who has visited Highline College in the past, and ask him how he put his new and selected collection together. Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems won the National Book Award, so I had the sense that he had gotten it right. I saw that he moved poems around, he didn't keep them in the original order that they were in the books. He wrote me, what I consider an essay, about the experience. Initially, he had sent an e-mail out to friends and said, “I'm putting together a new and selected, what should I include?” It wasn't helpful. He got answers like, “Oh this poem I read to my lover under an Elm tree in moonlight on our first date.” The other thing he said, that was helpful to me, was that no matter what you put in you will regret things that you include and you'll especially regret things that you don't include. In other words, you won't get it one hundred percent right.

Although, I have to admit he was right about that, it was freeing because there wasn't a perfect formula. Poems that were my particular favorites, for the most part, went in and there were certain things I wanted to make sure were represented. Cartographers Tongue was published in 2000 and Gallery Postcards and Maps came out in 2022. That's my first book to my most recent work.

I have lots of ekphrastic poems about different women photographers and different women artists and I wanted to make sure that they were included. The Irish way of publishing is so different from here, I was making additions and subtractions three weeks before the book went to press. There are some poems in there that were quite new. “Caravan” by Remedios Varo is the cover art for the book. I wrote a poem that's based on this piece. I felt that Leonora Carrington was getting more attention in the book than Remedios Varo and I wanted them to be equal as they were in life.

JG: In many ways, Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems documents a “map of my life” (taken from your poem “True Story”) and I am interested in how and why the threads of travel and cartography have remained constant in your work.

SR: It feels like [those threads] were much stronger, obviously, in Cartographer’s Tongue and also in Cures Include Travel, so I'm not sure what I have to say about that. I've lived in many different places. I've done human rights work in Gaza and the West Bank and in Bosnia. I was a Peace Corps volunteer in West Africa. I lived in England and Scotland in my early twenties, so in some way it's just literally where I've been and what I've done. I often say that travel was my drug of choice when I was younger. I didn't really feel like I ever belonged where I was and so I think there was a certain amount of searching, but also curiosity about the world, plain and simple. I was never very good at geography when we had that as a lesson in school, but once you go and live somewhere and you start having connections to different parts of the world geography becomes something very different than memorizing capitals for a test. A lot of my young adult life was lived outside the country and maybe that has given me an expanded worldview.

I just had a former editor of Arcturus write to me. I had invited her to come back for and launch party for the journal and she said she’s back in Nigeria now, so she couldn’t make it. She did her degree at Highline College and then she went on to the University of Washington and then her student visas ran out and she needed to go back to Nigeria. She's about to start her master’s degree in English Literature in Germany. I think I've stayed at Highline so long because there is an international presence just from teaching in the classroom.

I have a love of maps. I have a whole bookshelf full of books on different types of maps, not just the kinds we're most used to seeing. One of the first poems that I was really interested in was Elizabeth Bishop's poem “The Map.” I loved collecting international postage stamps when I was little, like really little, so these images and ideas came to me very young and for at least a decade, if not longer, I literally moved around to different places on the map. I'm not doing that anymore, though I still love to travel.

JG: I'm trying to remember that little Elizabeth Bishop poem “The Map.” I know I've read it but I'm curious about what you like about that poem or what stands out to you?

SR: Maps have to lie in order to get one dimensional. It's a very literal telling of the world, which immediately becomes metaphorical. Nobody would call Elizabeth Bishop a surreal writer and yet there's something about the way that she enlivens this object that feels surreal to me. The relationship between sea and land, for example. There is a lot in there about the painter’s colors. She's seeing the map as a work of art, as an object that allows for more than it can possibly tell us. It’s one of her early poems and I fell in love with that poem quite early on because I felt kinship to the way that she was understanding maps.

JG: I learned about or discovered female photographers and artists through your poetry. Why is ekphrastic poetry important to you? What can this form of poetry do?

SR: I was at the Frye Art Museum and I was waiting for my then boyfriend to finish work. It was raining, so I had to find a place to kind of go indoors and there was a hallway which is always kind of devoted to traveling photography shows. I just found myself in this little hallway and I was taken by this particular piece called “Hunger is the Best Cook” by Myra Albert Wiggins. I had never heard of her before. I thought I was looking at a painting and didn’t understand I was looking at an early photograph. I also didn't understand that it was constructed-- the four panes on the window were done with construction paper. She had built the rough table and her daughter was posed in old Dutch clothing. Myra Albert Wiggins lived in Oregon and in Seattle.

I didn't know any of this at that time. I just knew I was really taken by this piece and I literally jotted three lines about it, shut the notebook, and went off to meet my boyfriend. I didn't think about it again for a couple of years, until I was on a sabbatical from teaching, and I thought I'm going to go back to that museum and look at that painting and find out more about it. I got back there and a wonderful woman who worked at the gift shop said that the hallway always has traveling photography. Based on when I was there, she was able to tell me that was featuring northwest women photographers. She goes out in the back and comes back with the catalog for it which I bought. I was able to start thinking about Myra Albert Wiggins. Who was she? I found one biography on the internet and became enamored with her. She had a moment of glory, was connected with New York photographers, and she was shown once or twice with these major photographers. Then, the type of photography she did went out of fashion and that was the end of it. I have an article about this in the University of Oregon journal.

Hannah Maynard, the other photographer I have focused on, was from Canada and born in England. These were women whose work I found so amazing and yet I was coming across them in these very kind of odd ways. There's one book about her and I found it at the William James book shop in Port Townsend, looking through their photography section. I didn't go looking for it, I guess that's what I want to say, but it felt like an entree into the world of art that I never had felt before. I didn't grow up in a family that took me to art museums. I didn't grow up feeling like I belonged in an art museum, because I thought that was just for rich people.

By discovering these unknown women artists, who had the lives of artists way before I was born, was enchanting. It was like I got to go through a time tunnel and find that women had always been artists. Women had practiced art and I could, too. I wasn't intimidated by that. I wasn't going to write an ekphrastic poem about Picasso. That wasn't going to happen, but I suppose I felt like I was offering these women back into the world. It wasn't intentional, but it was extremely intuitive.

Time-wise, I think it was quite important because you write a book or two of poems and the world doesn't change the way you think that maybe it's going to change. We spend so long wanting to publish a book and hoping to publish a book and then you publish a book or two and the world pretty much stays the same. I was taken with the fact that this was historically true.

One of the early ways I came to Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo was through a wonderful book called Surreal Friends. These women, along with a photographer named Kati Horna, were friends and they were influenced by each other 's work and they hung out at the kitchen table and spent time together, smoked cigarettes together, drank together, and influenced each other’s ideas. I think there's one wonderful piece where Varo is wearing a mask that Carrington has created and the photograph is by Horna.

I just had never understood that this is the way some artists have always worked. The fact that I'm writing with Kelly or she and I together are starting Poets on the Coast or I have writing dates with other poets isn't weird. It made it feel like what we were doing had a tradition behind it that I'd never considered before. How do you make your life as an artist? How do you make a life as a woman artist? Where are the role models? Where is the underlying message that this has happened before, that this is a worthy thing to do, and that I'm not strange? I'm not strange for wanting to do this. It’s the long range plan, having a book or two, and then going on with other things in one’s life. My main identity is as a writer and it's taken me decades to claim that.

JG: I feel like what you just said was really profound and inspiring to me, too. I know you were saying there's sort of a long game to being a writer and I've had a relatively short publishing career at this point, with so many highs and so many lows. I struggle with that idea of “strangeness” too, so it was very comforting to hear you articulate that feeling. How does one really commit to their artist self and believe in the work?

SR: I was interviewed for the Arcturus journal this year since they decided to do interviews with a number of faculty. Since I'm an outgoing editor, they chose me. I wanted to say something smart, but one of the things I said is I have finally come to terms with the fact that poetry is my religion and that felt comfortable to me. I didn't add that I've never been a particularly religious person, because that would negate too much. But that's also true. I don't practice every day, I'm not doing my prayers in the morning. I'm not that person, but it is the way I understand the world. It is the way I look at the world and I also feel like it's been really important to me to have community. I'm putting Judaism and poetry into the same basket here. Many of the poets at Poets on the Coast say that when we write together as a group more exciting and wonderful things come out of them, than if you're in a room by yourself. I believe that. I don't know why it is, but I believe in that collective energy that helps us all. Poetry is one of the ways I make meaning out of my life. It also allows for endless curiosity no matter whether I'm interested in surrealist artists or science. I can't imagine not being a writer.

JG: You mentioned earlier that you will “have three books that will have come out in three years.” We have talked about Gallery of Postcards and Maps and Demystifying the Manuscript. Your new book of poems, Blue Atlas, is coming out in spring 2024. What is this book is about?

SR: My graduate school advisor was Garrett Hongo at the University of Oregon, and I told him about this experience. At the time of my abortion, I was twenty-six. My final MFA conversation with Garrett would have been thirteen years later, when I was thirty-nine. I don't remember how it came up, because it is not like we had chats about my personal life. He said that's what you should write about, that's the book you need to write. I looked at him like he was crazy, just absolutely insane. Why would I take the most painful thing that had ever happened to me, and the most private, and write poems about it? I remember his reply was “it's not just your story.” I couldn't understand that then, but it makes so much sense to me now that I have years of distance. The idea was planted. I just wrote him, recently, and said I finally took you up on that idea and it's the next book that I'm writing. It took ten years to write Blue Atlas and I'm still a little uncertain of what will happen when it comes out. Given how important a topic abortion is in our country right now, that is what made me think I should try to figure out some way to be part of the conversation.

Recent cover review for Blue Atlas on Lit Hub: lithub.com/exclusive-see-the-cover-for-susan-richs-latest-collection-blue-atlas/

Jessica Gigot

Jessica Gigot is a poet, farmer, and coach. She lives on a little sheep farm in the Skagit Valley. Her second book of poems, Feeding Hour (Wandering Aengus Press, 2020) was a finalist for the 2021 Washington State Book Award. Jessica’s writing and reviews appear in several publications, such as Orion, The New York Times, The Seattle Times, Ecotone, Terrain.org, and Poetry Northwest. She is currently a poetry editor for The Hopper. Her award-winning memoir, A Little Bit of Land, was published by Oregon State University Press in September 2022.

Susan Rich is the author of eight books including Blue Atlas (forthcoming from Red Hen Press), Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems (Salmon Poetry), Cloud Pharmacy, shortlisted for the Julie Suk Award, The Alchemist’s Kitchen, named a finalist for the Foreword Prize and the Washington State Book Award, Cures Include Travel, and The Cartographer’s Tongue, winner of the PEN USA Award. Along with Brian Turner and Ilya Kaminsky, she edited The Strangest of Theatres: Poets Writing Across Borders (Poetry Foundation) and just this year, Demystifying the Manuscript: Essays and Interviews for Creating a Book of Poems (Two Sylvias Press), co-edited with Kelli Russell Agodon. Rich is a professor at Highline College in Seattle, WA. She offers an annual poetry retreat for women called, Poets on the Coast.