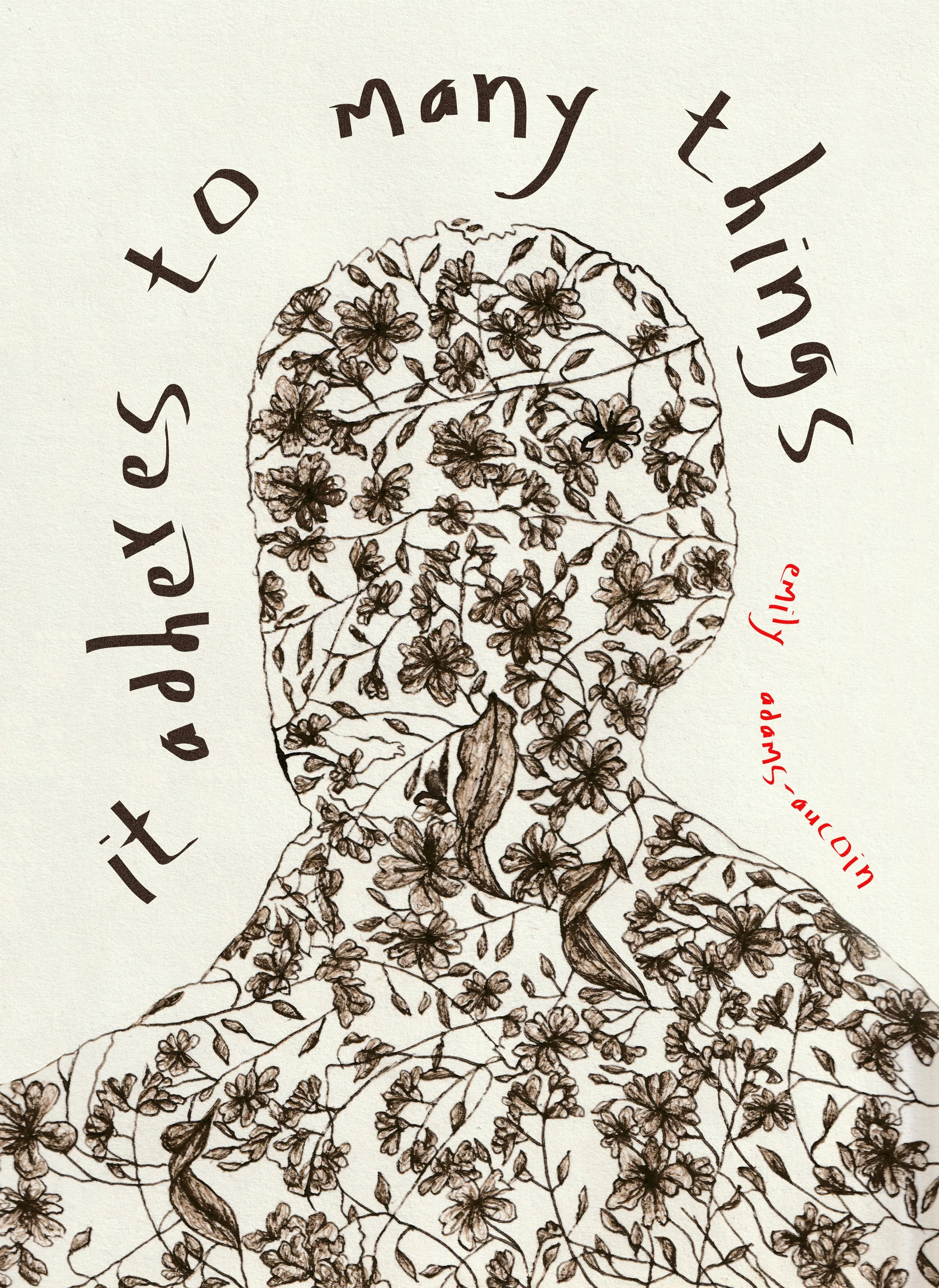

Cover art: Untitled

Artist: Diana Baltag

Foreword

What follows in Emily Adams-Aucoin’s “It Adheres to Many Things,” are a series of poems holy or broken, as in Leonard Cohen’s lines: “There’s a blaze of light in every word / it doesn’t matter which you heard, the holy or the broken Hallelujah.” From the idea in the first poem that, “Not even a perfect thing plus a perfect thing equals happiness,” to the notion in her penultimate poem, “...Nothing / answered, which was a kind / of answering,” Adams-Aucoin guides us into her personal journey through lenses alternatively saintly and monstrous.

Within its brief beauty, It Adheres to Many Things speaks to the individuated language of self-reflection, creating from its whole a kind of hapax legomenon, a unique word within the context of itself. “I thought the world would be more beautiful / after I studied it,” she writes. “For a brief moment, / everything was alive, illuminated.” And indeed, Adams-Aucoin gives us this holy or broken (or both) world in its own tongue, a world illuminated and staring back at those who dare to look.

Gregory Stapp

2025

IT ADHERES TO MANY THINGS

Table of Contents

1. Melencolia I

2. The Monstrous Sow of Landser

3. The Ravisher

4. The Angel with the Key to the Bottomless Pit

5. St. Jerome in His Study

6. The Elevation of Saint Mary Magdalen

7. The Witch

8. Virgin with Hairband on a Crescent Moon

9. Agony in the Garden

10. Madonna with the Pear

“What beauty is, I know not, though it adheres to many things.”

—Albrecht Dürer

They were melancholy-textured hours. Our old dog was skin and bone,

officially resigned. I had golden keys which unlocked nothing.

It wasn’t night, but there was a kind of persistent half-sleeping;

my mind pushed against the bars of itself in a perfunctory way.

An angel mourned the world with me, which compounded

the mourning—that the angel was there and that it could speak,

but that it wouldn’t speak to me, not even in a language

I could learn with goodness or waiting. There’s a lack of purpose

in the sadness, a hole in that dark fabric through which I can see myself.

Not even a perfect thing plus a perfect thing equals happiness.

To be winged and not flying, to have the tools and let them rust

at your feet. What is that called, besides love of potential energy?

Don’t tell me. It must be true that someone watches, calculates, collects.

To be an artist is to have your creation stare back into you with

the grotesque eyes you gave it.

Monster: the awful intersection of

other and fear. Once, I was a monster,

though it was never my official name.

When I read about the two-bodied pig,

I felt only pity, not wonder or

fear. I was too familiar to be scared.

Two heads is a sign from God. Two bodies

is the Earth burdening you because it

can. The pig lived one day, doubly shackled.

Not twice the stars, or twice the persimmons

on the trees, just all that blood rushing the

distance. I called my mother to tell her,

but she already knew. Imagine that,

she said, two bodies. But no, I couldn’t.

My single body was humming too loud.

Of course Death would come to me

like a fucking man. To fight him off,

I had to use the hands that I loved with—

the exact same hands. I’d spent years walking

the perimeter of that placid lake, assuming it was safe

because it’d once been safe. Then, a man came to me

like Death. By then, I’d sacrificed so much

to the old gods of childhood. The years were fat,

docile animals in my lap. I was angry

when he touched me because I stupidly

thought I’d earned protection. I’d rounded

up for grocery store charities, held my outraged

tongue, and drank sparingly. But none of it mattered.

The world still thistled and thinned to transparency.

The air contained a sudden, strange electricity.

I used to be a materialist, which was almost enough.

Then he came for me.

THE ANGEL WITH THE KEY TO THE BOTTOMLESS PIT

As punishment for my crimes, I had to give up the bright world

and live below the threshold of good, which didn’t mean it was bad

necessarily, but that the constructs of good and bad couldn’t stretch

that far down without thinning beyond recognition. The angel

reminded me, but I already knew the deal—a thousand years

with only the company of my desire, which, in the pit, would sharpen

against the dark. The angel warned me with its deep voice: I would have to

press myself against the damp walls to keep it from cutting me. The doors

of my heart would close and then open and then close again.

When it was time for me to climb back out, the angel said, the world

would be different—in my absence, it would fall further into entropy,

dividing again and again against itself until there was no part of it

that wasn’t also in me, and no part of me that I couldn’t find in it.

Oh, what terrible homogeny! Before it pushed me in, the angel kissed me.

Yes, I know what I’m made for.

How to be saved, except by the truth?

At this time of year, the trees don’t fruit.

The leaves grow to the size of a palm

and it doesn’t mean anything. For a decade,

I saw colored halos of light around people.

Someone told me it was a divine gift.

Someone else said it might be brain cancer.

One day, I woke up and it was gone,

and I grieved that strange sight terribly.

A library in my head had been incinerated.

And what, then, had my crime been to deserve

this long, colorless sentence? Once, I knew

what I was—it eddied around me, glittering.

The evidence cataloged itself by hue.

I thought the world would be more beautiful

after I studied it. For a brief moment,

everything was alive, illuminated.

And then everything dimmed.

THE ELEVATION OF SAINT MARY MAGDALEN

But one day, I woke to find it was like this:

winged babies at my feet, grabbing at me from beyond

the cold veil, hoisting me from underneath.

When they spoke, it was in a wordless language

like laughter. True that I could have fought harder,

could have refused their precious tyranny,

but they cooed so sweetly, and hooked their talons

into my sides. I took the job because it was asked of me.

No—I took it because I wanted to ask the job

about myself. Like any other job, it has its perks.

The sweetness of the hours, vacuous and syrupy.

Really, it’s more like the job took me.

At the first signs of crow’s feet, I spend two hundred dollars

on serums with hyaluronic acid and retinol. My skin is always

wet and shining. Youth is an old god that demands sacrifice.

In the half-dark, I’m beautiful, but it’s such a slight beauty—

you have to tilt your head. I use light and angle strategically.

I forget what I really look like so that when I accidentally

see my reflection, I scream, as if I’m an intruder

in my own home. I think:

if there were no mirrors, I might be able to convince myself.

Then the mirrors screw themselves further into the walls.

Every night, I dream of flying backwards on a black goat

who’s singing. My crow’s feet grow bodies,

and then beaks, and then wings.

VIRGIN WITH HAIRBAND ON A CRESCENT MOON

Below us

is the sleeping world,

which I look upon

from our thin moon

like a jealous God.

Everywhere I look,

I find the absence

of myself. I do the dishes,

fold laundry, confront

oblivion. Even the birds

are quiet at midnight,

as quiet as my heart.

In the dark, we become

animals again. We speak

without speaking,

sing without music.

Everything that makes us

human falls away

like a delicate husk.

The night used to be

mine to spread out in

as I wished, and now

this reconfiguring.

The hours go by

like icy centuries.

Sometimes

in my dreams, I sleep.

I went to the garden to pray in my

awful way. It sounded like begging

because it was begging. The silence

filled the spaces like agonizing

music so that I couldn't hear

what the instructions were—

I couldn’t even imagine

what they might have been.

I said, If I must finally forget myself,

and If I must stay in the world

and bend myself and not it, fine.

But my hands trembled. The quiet

crescendoed not in volume

but in meaning. All around me,

the leaves shook with silent,

self-assured laughter. Nothing

answered, which was a kind

of answering.

Those months were pools of thick mud I waded through.

I could’ve been sleeping, but I wasn’t. None of the relief

from leaving the dream. With one arm, I carried my daughter,

my legacy of how I eventually decided to love the world.

With the other, a ripe, yellow-green pear heavy for its size.

I was leaving, then, which explained the resistance. Leaning

against the knotted flesh of a leafless tree, I knew I was lucky,

even as the mud eveloped my ankles, fed with icy water

from the nearby sea. It was winter, and I still had

sweetness. My daughter cooed to me in our language.

I took a large bite of the pear, and the juice dripped down

my chin. Mud rose to my ankles, then my shins. Believe it

or not, that was higher ground. There was nowhere else

to climb to. We were lost in the wet and dark of December.

We had to wait there for the light.

Acknowledgements

"Melencolia I", Shō Poetry Journal Issue Seven (June 2025)

"Madonna with the Pear”, The Columbia Review (Spring 2025)

IT ADHERES TO MANY THINGS

Copyright © 2025 EMILY ADAMS-AUCOIN

Cover art by Diana Baltag, "Untitled", 2020.

Cover and interior design by Diana Baltag

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or republished without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Harbor Review

Joplin, MO 64870

harborreviewmagazine@gmail.com

www.harbor-review.com

Emily Adams-Aucoin is a writer whose poetry has been published in Electric Literature, Frontier Poetry, TriQuarterly, Sixth Finch, North American Review, Colorado Review and elsewhere. She’s a poetry editor for Kitchen Table Quarterly, and you can find her on social media @emilyapoetry.