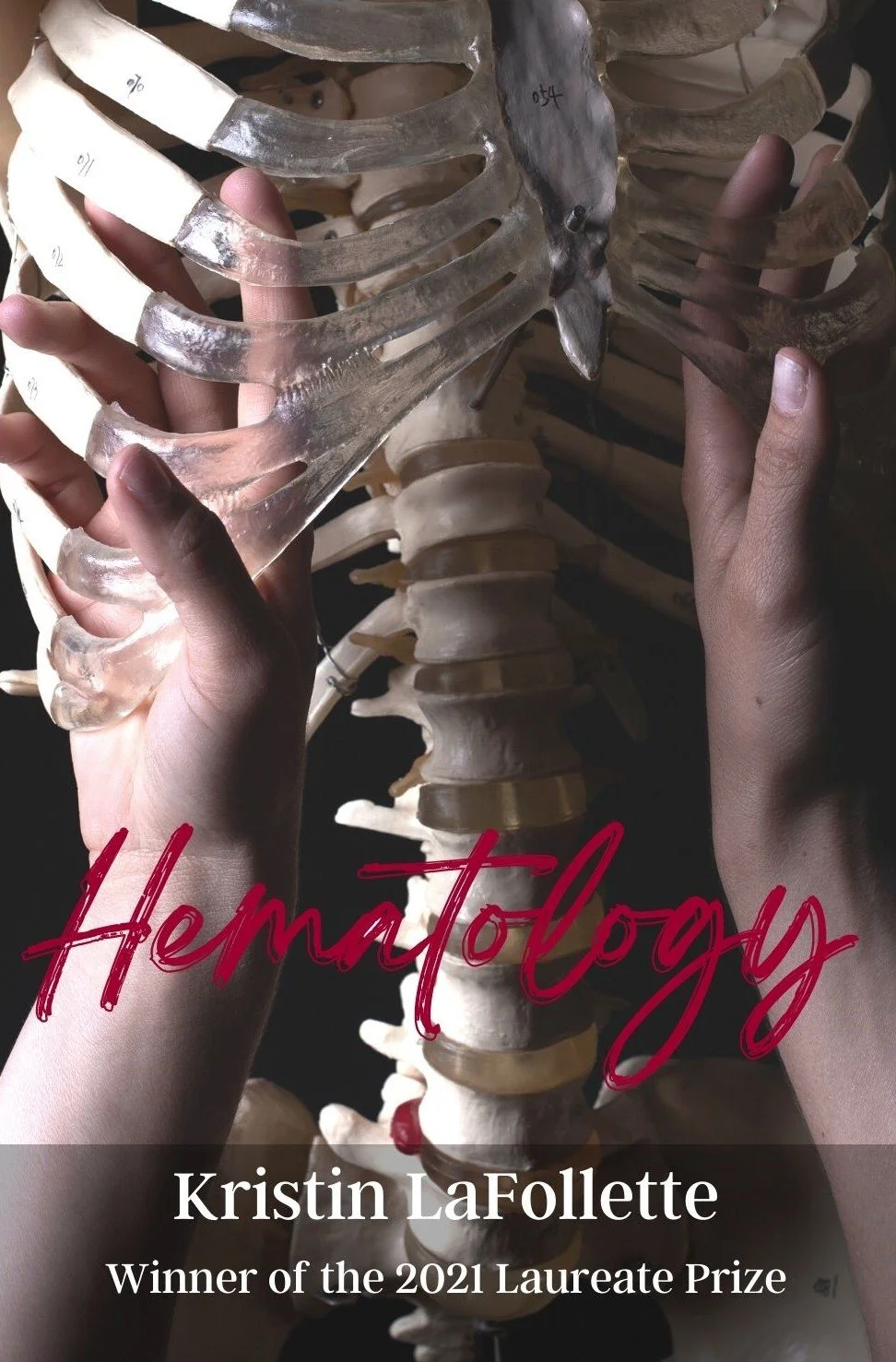

Hematology by Kristin LaFollette

Reviewed by Kristiane Weeks-Rogers

Hematology by Kristin LaFollette is the 2021 winner of Small Harbor’s Laureate Prize. As the title indicates, this collection borrows the studious frame of the doctor, or medical field, and explores the physiology of blood. The larger figure of blood threaded through this collection flows into an exploration of familial relations: blood and non-blood. LaFollette opens the collection boldly with a poem about hunting. From “Women”:

I grew up unafraid of guns because you

taught me not to be afraid:

Hunting is eating &

together we find and take the marrow—

As a child you took me with you

to the woods to help pull an animal

into the back of the truck, drape it with a blue

tarp, watch as the others washed the blood and

mineral off their hands with cool water from a jug

This opening poem immediately presents a lifestyle and the context of a people who have a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between nature, humankind, and machine. This context tells us guns are part, not a focal point, of the hunting culture. We also start to see how blood is going to be studied in Hematology primarily outside of medicine, in the environments we grow from. As the speaker notes in “Heirloom,” “My descent is of water and corn … .” Where there are cornfields and woods, where there are deer and small game around fresh water rivers and lakes, there is a hunting lifestyle.

The tone is dense like a Midwestern haze in Hematology. The division into three parts provides a space to pause between sections. LaFollette also alleviates the overall heaviness by softening the language around experiences of blood. In “The Organism’s Phenotype”, for example:

I’ve always known

the colors of blood

In a field

near our house:

A deer with its organs

removed by my father’s

hands—

The purple-red meat,

a damp smell like

brown leaves

and bath water.

Deer blood is the focus of this scene— and maybe this image isn’t for the faint of heart— but there’s a sense of warmth provided in the red and purple hues described. The smell isn’t gross or sour, it’s described as gentle things; wet leaves and bath water, which is calm. There’s an appreciation in this scene with the speaker’s father, multiple layers of relationships being formed and growing.

The relationship between human and deer develops through Hematology, too, beyond the hunting perview. There are moments LaFollette twists the relationship of human and deer, to blend these separate bodies and their blood together, “Like you, / I am a human / being with / antlers / for / bones” (A Kind of Sympathy). The antlers are human, inside the body, solidifying this notion that deer and humans create one body. With this mixing, the deer and the human body are one and the same, where even the speaker attempts to identify the separation through “The human kind, but easily / mistaken for deep blood, / stringy red velvet hanging / from antlers, red against / all that green—” (A Confession, Part I). LaFollette adds a surrealist aspect to the human and nature relationship. With a striking image of green against green like an Argento giallo film, we see the image of human blood hanging off antlers, as if antlers were part of this body, the blood from the same body. Blood physiology doesn’t need to be studied by doctors, Hematology shows how blood is a common denominator between man and nature, and that is enough to treat all beings as your own flesh and blood.

The themes shift away from hunting in Parts II and III, yet contain its blood and bone and bodies, its observation of bodies in change. “When you have no choice, / you can make your body do / almost anything” (Ambidextrous). Biblical allusions bring gravity to this section: “The Washing of the Bodies” ends with, “Here we break bread.” “Something in the Water” describes a time where the speaker “saw God in a handprint / stamped on a sheet of paper / in green paint.”

As we continue to see earthy hues of green, even more biblical themes pile on, involving repentance as well as water. Part II bridges our way to the final and weightiest of LaFollette’s subjects: Part III, which mourns and copes with a sibling’s death, pulling together all the preceding themes of color in bones, bodies, blood, and concludes in, “After My Sister’s Passing”: “Even still, I won’t forget the color of her bones— / I’ll remember that I don’t have to see chrysanthemums and / orchids to know the papering of words….”

Kristiane Weeks-Rogers

Kristiane Weeks-Rogers (she/her/hers) is a Poet-Writer living in western Colorado. Her debut poetry collection, Self-Anointment with Lemons, was released September, 2021 by Finishing Line Press. She is the 2nd place winner of Casa Cultural de las Americas and University of Houston’s inaugural Poetic Bridges contest, and author of the chap collection Become Skeletons published by the University of Houston in 2018 as reward. She grew up around Lake Michigan and earned her higher education degrees in Florida (Flagler College) and Indiana (Indiana University). She earned her MFA at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, Colorado.